HTML and Templates & JavaScript Template Literals

Ada Rose Cannon

Web Developer Advocate

HTML in the Web is often made of reusable components, composed by templates, making it convenient to edit the different parts that make up a website. There are many templating languages used in the web such as handlebars, Pug, Vue and JSX; these are primarily used for composing HTML. Modern JavaScript has templating syntax built in which can use for all kinds of purposes including composing HTML.

In this post I will introduce the JavaScript syntax for templating and then show how it can be used in the real world for sanitising HTML and introducing some of the frameworks which use template literals for their templating.

Template Literals are a really nice JavaScript feature you may not have used much yet, they look a bit like strings:

const message = `Hello World`;

message === "Hello World"

You can include new lines:

const message = `Hello

World`;

message === "Hello\nWorld"

You can use the dollar-curly-brace ${} syntax to inject variables:

const name = 'Ada';

const message = `Hello ${name}`;

This works really well when combined with Arrow Function Expressions to make templating functions, which turn the arguments into a string:

const messageFn = name => `Hello ${name}`;

const message = messageFn("Ada");

Tagged Template Literals

You can put a tag on a template to transform the template before it gets turned into a string.

The tag is a function which is called with the first argument being an array of the rest of the arguments are the values of the place holders. In the example below we use the rest parameter to put all of the place holder arguments into an array.

There is always one more string than the number of placeholders. You can reassemble the output by interleaving these Arrays such that for a template with N placeholders the output is:

strings[0] + placeholders[0] + strings[1] + placeholders[1] + … + strings[N] + placeholders[N] + strings[N+1];

This is what is looks like in JavaScript:

function myTag(strings, ...placeholders) {

const N = placeholders.length;

let out = '';

for (let i=0; i<N;i++) {

out += strings[i] + placeholders[i];

}

out += strings[N];

return out;

}

const message = myTag`Hello ${1} world ${2}.`

This function is equivalent to the String.raw function which is the default behaviour for template literals.

const message = String.raw`Hello ${1} world ${2}.`

You can also use String.raw inside your custom template tag to regenerate a string. In the example below we check the input to make sure it’s a string then use String.raw to output the data as a String.

function myTag(strings, ...placeholders) {

for (const placeholder of placeholders) {

if (typeof placeholder !== 'string') {

throw Error('Invalid input');

}

}

return String.raw(strings, ...placeholders);

}

Your tagged template literal doesn’t have to return a String it can return what ever you need, here is a very simple tag which measures the length of the input:

function myTag(a, ...b) {

return String.raw(a, ...b).length;

}

HTML & Tagged Template Literals

Template literals are great for HTML because you can add newlines and very cleanly have dynamic classes and other attributes.

const myHTMLTemplate = (title, class) => `

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head><title>${title}</title></head>

<body class="${class}">

...

`;

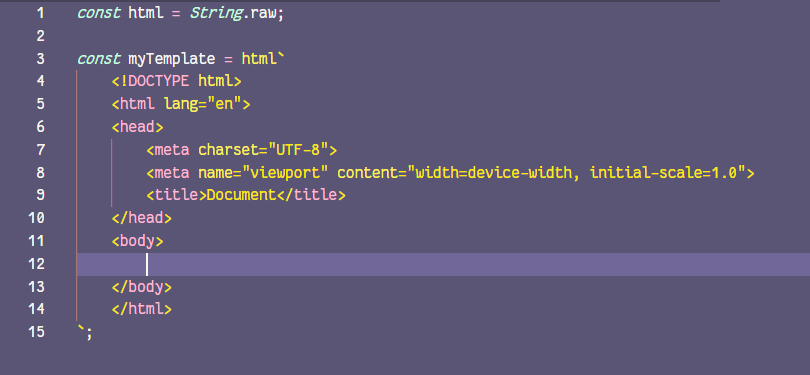

If you use Visual Studio Code the Lit-HTML extension will add syntax highlighting and HTML intellisense features and emmet shortcuts for templates tagged with a tag called html . The html tag doesn’t have to be the one from the lit-html library even using String.raw will give you the really nice features of HTML inside a JavaScript or TypeScript file.

HTML syntax highlighting in a JS file

HTML syntax highlighting in a JS file

Sanitising HTML with a Tagged Template Literal

When you are outputting HTML that may contain user generated content you have to be careful about malicious JavaScript users may try into inject into all kinds of elements, these kinds of attacks are known as cross-site scripting aka XSS.

It’s best to strip out dangerous elements and attributes. You can do that in a template literal tag using a library like html-parser2.

We want to have two types of input into the placeholder, raw text strings which needs sanitising and safe HTML which is either authored by us or has been put through the sanitiser. This class just stores a string and we can use it to mark strings that are safe.

class SafeHTML {

constructor (inStr) {

this.string = inStr;

this[Symbol.toPrimitive] = function (hint) {

return this.string;

}

}

}

Then we have our template literal tag function, this does nothing to SafeHTML objects and sanitises raw strings returning a new SafeHTML from our template literal.

const html = (stringArray,...placeholders)=>{

const sanitisedHTMLArray = placeholders.map(

p => p instanceof SafeHTML ? p : stripHTML(p)

);

const out = String.raw(stringArray, ...sanitisedHTMLArray);

return new SafeHTML(out);

}

To strip the HTML first I listed all the elements I wanted to allow and the attributes which are safe, these are mostly all used for formatting or semantics.

const allowedTagAttributes = {

a: ["href"],

b: [],

i: [],

img: ["src", "alt", "title"],

abbr: ["title"],

ul: [],

li: [],

h1: [],

h2: [],

h3: [],

h4: [],

h5: [],

h6: [],

hr: [],

figure: [],

figcaption: [],

p: [],

u: [],

s: [],

ruby: [],

small: [],

span: [],

del: [],

strong: [],

table: [],

thead: [],

tbody: [],

tr: [],

td: [],

time: [],

ol: [],

};

const allowedTags = *Object*.keys(allowedTagAttributes);

Then we use htmlparser2 to go through the input text string and rebuild the HTML string using just the allowed elements:

function stripHTML(inStr) {

const textOut = [];

const parser = new htmlparser2.Parser(

{

onopentag(tagname, attribs) {

if (allowedTags.includes(tagname)) {

const allowedAttribs = allowedTagAttributes[tagname];

if (tagname === "a") {

attribs.href = sanitiseURL(attribs.href);

}

textOut.push(

`<${tagname} ${

allowedAttribs

.map((key) => attribs[key] ? `${key}=${attribs[key]}` : "")

.join(" ")}>`

);

}

},

ontext(text) {

textOut.push(text);

},

onclosetag(tagname) {

if (allowedTags.includes(tagname)) {

textOut.push(`</${tagname}>`);

}

},

},

{ decodeEntities: false }

);

parser.write(inStr);

parser.end();

return textOut.join("");

}

When we use the html tag function we just created we can now seperate our authored HTML from users unsafe HTML.

const unsafe = `<img onmouseenter="location.href='[https://example.com'](https://example.com')" src="[http://placekitten.com/200/300](http://placekitten.com/200/300)" />`;

const safeHTML = html`

<style>

div {

color: red;

}

</style>

<div>User Content: ${unsafe}.</div>

`;

Using template literals with JS frameworks

If you need more functionality than basic templating there are some really light and fast frameworks which use template literals.

lit-html is pretty well known and designed to work with the polymer web component framework.

Polymer/lit-html

lighter-html is designed to be really fast and very small. It’s really well featured and a great way to build a really fast web site.

WebReflection/lighterhtml